[S01.5] Non-religious Spiritual space for social cohesion in Vietnam

Abstract

Chapter 1: Land and People

Chapter 2: Non- religious spiritual space within the framework of social concerns

Chapter 3: Collective- cultural memory and social cohesion

Chapter 4: Case studies

Chapter 5: Design Solution

Chapter 4. Case Studies

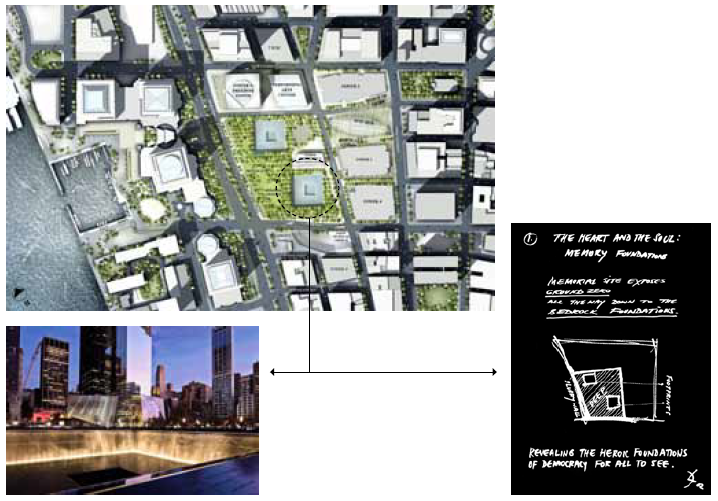

4.1 Berlin Jewish Museum and Ground Zero- the void of collective memory

In The destruction of memory- Architecture at war, Robert Bevan observes how collective memories embedded in buildings through the architectural destruction as ethnic cleansing. Even though, the buildings do not have their own memories but they do carry the memories of a community invested in them. This investment is the reason for their very existence in a societal context. Therefore, the demand for preservation or reconstruction is a natural reaction to protect memory. Collective memory, however, is a continuous process rather than a result at a certain point. Therefore, in some cases, the rebuild of a destroyed building may encourage the forgetting of its presence (Bevan 2006). In this regard, the concept for the Ground Zero memorial in the World Trade Center is not to fill the void but to reserve its absence. The Memorial consists of two large square pools with waterfalls cascading into the centre. Most of the site is devoted to the public visually and acoustically by the foliage and the sound of the waterfalls while the new buildings are put on the periphery. The memory of the place is recalled and reconstructed by the memorizing of its own community.

Figure 02 (right, above). Libeskind’s hand sketch explains the meaning of the “void” (Vinnitskaya 2012)

Figure 03 (left, below). The waterfall pool (Vinnitskaya 2012)

“it is not only the visible, apparent history that you can photograph, but it’s the non-apparent history that is to do with the people whose voices are still there.” Daniel Libeskind

In the case of the Jewish Museum Berlin, traumatic memories about the Holocaust is interpreted by silence and emptiness. As one of the first “experimental museum”, the inauguration of this museum was in fact marked by the construction completion in 1999, long before the emergence of exhibitions inside in 2001 (Reeh 2016). At that time, the building was opened and exhibited for the public visit as an entity itself.

The museum surprises the visitors by the distinct contradiction of two freestanding structures in the appearance between the old and new, the classic and modern but deeply connected to each other by an underground entrance from the existing building to the extension museum (figure 04, 05).

The whole journey is divided into three different routes that each of them will end up with a singular destination: The Garden, The Holocaust Void and the Memory Void. These spaces I would define as a spiritual space in which its story is told by the place itself.

The Garden is an upside-down outdoor space with 48 concrete columns on the sloping surface.

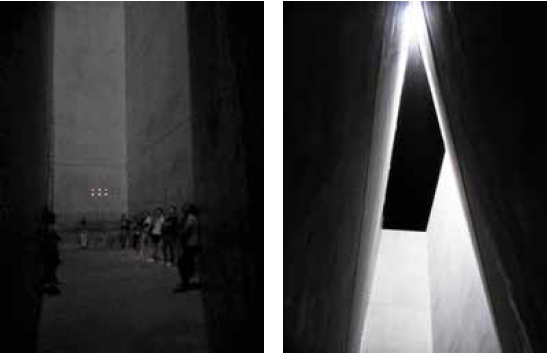

The Holocaust Void is a completely plain room, 27 meter high (figure 07). When the heavy metal door is closed behind, the visitors are suddenly embraced only by the darkness. The natural reactions are recorded

from most of them is looking up to search for the only source of natural

light coming from a narrow line in the ceiling (figure 08, 09). People, for the

first time perhaps can experience a real-time prison as a forever dead end

in the journey of the murdered Jewish.

Figure 08. The reaction of visitors inside the space.

Figure 09. Natural light from the ceiling.

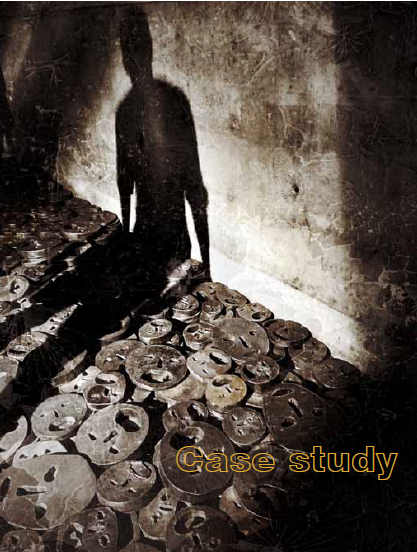

The Memorial Void (figure 10) is a space “between the lines”, its floor is covered by over 10,000 faces of soundless screams (the Fallen Leaves). This space is described as a living creature awaken by the interaction of the visitors with the installation: the echoes of clanging sounds when they step on the metal pieces recall a sense of exile (figure 11).

There is no specific answer for all of these experiences which can only be filled in by personal emotions. In other words, the visitors are free to feel and memorize the place by all of their senses and their emotions become a sole string tieing them to the space. In this regard, the meaning of a collective memory does not rest on the past but always exists in the present as a succession. Therefore, a design for collective memory should come from the respect of its own reality.